L’attenzione

Tra i danni più frequenti nella sfera cognitiva si collocano i deficit di attenzione, dei quali però non è stata ancora determinata in modo unanime l’esatta frequenza. Uno studio del 2013 (Loetscher T et all, 2013) riporta una percentuale che varia in un range tra 46 e 92% nella fase acuta (Stapleton T et all, 2001) e tra 24 e 51% al momento della dimissione dall’ospedale (Hyndman D et all, 2008). Comunque ciò che possiamo affermare con certezza è il fatto che l’incidenza dei deficit di attenzione conseguenti all’ictus è molto elevata, e Goldberg ne illustra in maniera convincente i motivi. “L’attenzione può essere descritta bene come un circuito che comporta interazioni complesse fra corteccia prefrontale, regioni ventrali del tronco encefalico, e corteccia posteriore. Un collasso, a qualunque livello in questo circuito, può interferire con l’attenzione producendo così una forma di deficit. La prima conseguenza della precedente analisi è che il deficit di attenzione è fra le più comuni ripercussioni delle lesioni cerebrali” (Goldberg, E, 2004. Pag. 198).

I deficit dell’attenzione si manifestano con un’ampia varietà di sintomi, come ridotta capacità di concentrazione, distraibilità, riduzione del controllo degli errori, difficoltà a fare più di una cosa contemporaneamente, lentezza mentale e faticabilità (Loetscher T et all, 2013).

Si tratta di limitazioni che incidono gravemente sulla vita quotidiana dei soggetti colpiti. E’ stato dimostrato, ad esempio, che i deficit dell’attenzione nelle diverse componenti possono contribuire a generare un comportamento incline a causare incidenti, con particolare riguardo a cadute accidentali (Hyndman, D. et all, 2003) e sono inoltre associati con il controllo dell’equilibrio e il functional impairment (Stapleton T et all, 2001).

In particolare McDowd (McDowd, J et all, 2003) et al. suggeriscono come deficit dell’attenzione alternata e dell’attenzione divisa, spesso compromesse nell’ictus, ostacolino gravemente la partecipazione sociale e che anche un lieve deficit di queste funzioni abbia un inpatto negativo di grande rilievo e pertanto suggerisce che questi deficit vengano trattati in modo specifico nell’ambito della riabilitazione post-ictus.

Sappiamo inoltre che, essendo l’attenzione coinvolta in molti processi mentali, un suo deficit può avere un impatto negativo su altre funzioni cognitive come il linguaggio, la memoria (Lezak M et all, 2004) e in ogni forma di apprendimento (Roberson IH et all, 1997.

In particolare sembra che un ruolo preponderante venga svolto dall’attenzione sostenuta, che risulta essere per gran parte una funzione dell’emisfero destro (Bench C. J. Et all, 1993) ed è un importante fattore predittivo per il recupero funzionale (Ben-Yishay et all, 1968). Sebbene dalla letteratura emerga che i deficit dell’attenzione in alcuni casi (Hochstenbach, J. B. et all, 2003) possono regredire con il tempo, di fatto l’importanza dell’attenzione ai fini del recupero funzionale suggerisce la necessità di un intervento precoce sulla sua riabilitazione. Tra l’altro nel 20-50% dei casi questi deficit sembrano persistere per anni nei pazienti sopravvissuti all’ictus (Barker-Collo S et all, 2010).

L‘identificazione precoce e la riabilitazione dei deficit di attenzione dopo l’ictus sono sostenute vigorosamente dalla American Heart Association (Duncan PW et all, 2005).

L’ATTENZIONE

L’attenzione, che intuitivamente sembra essere un processo molto chiaro, è in realtà un fenomeno molto complesso. Nel 1890 William James scriveva:

“Tutti sanno che cosa è l’attenzione. Essa è la presa di possesso da parte della mente, in forma chiara e vivida, di uno di quelli che sembrano molteplici simultanei oggetti o flussi di pensiero. Focalizzazione, concentrazione della coscienza sono la sua essenza. Questo implica il ritrarsi da alcune cose allo scopo di trattare efficacemente con altre, e è una condizione che trova il suo reale opposto nello stato confuso, stordito e sbandato che in francese è detto distraction e in tedesco Zerstreutheit ”.

E’ notevole che James avesse intuito che l’attenzione opera non solo nel flusso sensoriale, ma anche nel flusso dei pensieri (Raz, A et all, 2004). Grossolanamente possiamo dire che l’attenzione è un processo attraverso il quale vengono selezionati aspetti dell’ambiente o idee immagazzinate nella nostra mente al fine di riservare a questi, e a questi soltanto, le risorse computazionali. Il processo di selezione è indispensabile per la limitazione delle nostre risorse computazionali (Broadbent DE, 1958).

Spesso per definire l’attenzione utilizziamo metafore tratte dall’esperienza visiva, che è di gran lunga la più importante e la più studiata nell’uomo; si parla pertanto di fascio luminoso, riflettore, zoom, fuoco, tutte metafore che forniscono una visione intuitiva. In effetti è possibile scegliere se esaminare un ambiente in modo panoramico o se zoomare su aspetti particolari o spostare lo sguardo da un oggetto all’altro.

Per altro anche nella modalità auditiva possono operare analoghi meccanismi attenzionali: nel Cocktail party, ad esempio, possiamo percepire globalmente il chiacchierio in una sala dove si svolgono più conversazioni o possiamo concentrarci sul nostro interlocutore, lasciando tutto il resto sullo sfondo. E’ anche possibile spostare l’attenzione da uno stimolo uditivo ad un altro, cambiando interlocutore. Nel caso dell’udito possiamo anche spostare l’attenzione da un orecchio all’altro come avviene nell’ascolto dicotico.

(…) La prima formulazione della complessità del sistema attenzionale risale all’articolo di Posner del 1971(Posner M. I., 1971) (…). (…). In un articolo fondamentale del 1990 Posner e Petersen (Posner, M. I. et all, 1989) stabilivano (che) (…) l’attenzione è attivata da una rete di aree anatomiche, (…). Gli autori individuavano tre funzioni distinte, (..)collegate a tre distinte reti neurali. Il modello proposto è stato da allora corretto e raffinato, ma conserva ancora l’originaria impostazione: tre reti per tre distinte funzioni, alle quali oggi ci riferiamo solitamente come alerting, orienting e executive:

· alerting (vigilanza), la cui funzione consiste nell’attivazione e nel mantenimento dello stato di allerta

· orienting, che è il processo attraverso il quale viene selezionata l’informazione nel flusso sensoriale

· executive, che è il meccanismo deputato a monitorare e risolvere conflitti tra pensieri, sentimenti e risposte.

PRINCIPALI METODOLOGIE RIABILITATIVE

Le diverse metodologie standardizzate sono indispensabili per un approccio serio al problema della riabilitazione, ma la loro funzione è solo quella di fornire una cornice, all’interno della quale risulta piena responsabilità del terapista tracciare un percorso riabilitativo fortemente personalizzato per ciascun paziente (Michel, J. A. et all, 2006).

Le principali metodologie per la riabilitazione dei deficit di attenzione sono l’ Attention Process Training (APT), Time Pressure Management (TPM), il Training di specifici skills e il Working Memory Training (VMT).

ATTENTION PROCESS TRAINING (APT)

L’A.P.T (Haskins EC et all, 2012) è un programma strutturato di training dell’ attenzione elaborato da McKay Moore Sohlberg e Catherine A. Mateer.

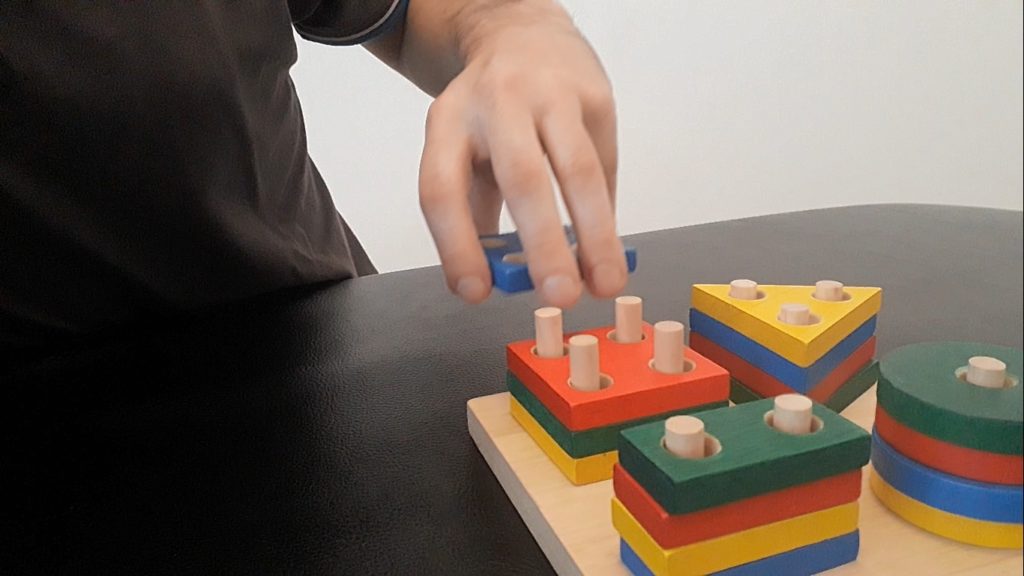

Esso si basa su un modello clinico dell’attenzione, che individua cinque distinti tipi di attenzione : attenzione focalizzata, sostenuta, selettiva, alternata e divisa.

· L’attenzione focalizzata è la capacità di rispondere distintamente a specifici stimoli sensoriali (visivi, auditivi, tattili). (…)

· L’attenzione sostenuta è la capacità di mantenere una risposta comportamentale coerente durante un’attività continua e ripetitiva. In essa si ravvisano due distinte componenti: la vigilanza e la memoria di lavoro. La perdita della vigilanza comporta l’incapacità di conservare coerenza di risposte per più di un breve periodo di minuti o secondi. Il deficit nella memoria di lavoro implica incapacità di manipolare l’informazione e conservarla nella mente.

· L’attenzione selettiva è la capacità di (portare avanti un compito), malgrado la presenza di stimoli distrattivi o competitivi, esterni (sensoriali) o interni.

· L’attenzione alternata (…) (è la possibilità) di focalizzarsi di volta in volta su compiti distinti che richiedono competenze cognitive diverse.

· L’attenzione divisa (…) (consente di) rispondere simultaneamente a molteplici compiti. (…).

Nell’Attention Process Training:

· I task del training devono seguire un ordine gerarchico. Quando e solo quando un paziente ha acquisito la capacità di svolgere un determinato esercizio, il trattamento passa a livelli di complessità più elevati.

· La ripetizione del compito e l’esercizio intensivo sono requisiti essenziali affinché il paziente acquisisca la capacità di svolgerlo correttamente.

· Il training dell’attenzione dovrebbe includere compiti che promuovano la generalizzazione delle strategie. Metterle in pratica in altri contesti è un passo fondamentale ai fini della generalizzazione.

TIME PRESSURE MANAGEMENT

I pazienti che hanno avuto un ictus o un trauma cranico presentano spesso un rallentamento nel processamento delle informazioni, in particolare quando sono sotto pressione o hanno un tempo limitato per svolgere un’attività. Si determina un sovraccarico per le funzioni cognitive.

Il T.P.M. (Haskins et all, 2012) propone strategie strutturate di problem-solving che consentono un controllo ed una regolazione degli input delle informazioni (Fasotti et al, 2000). Il TPM allena i pazienti a prendere per tempo le decisioni necessarie sia prima che durante lo svolgimento di un compito. Gli autori hanno identificato tre livelli di approccio:

Decisioni strategiche. Una pianificazione preventiva del compito da svolgere aiuta a bilanciare e minimizzare i problemi che questo può comportare. Risulta fondamentale per evitare un sovraccarico nell’elaborazione delle informazioni.I

Decisioni tattiche. Necessarie quando occorre apportare delle modifiche alla pianificazione durante lo svolgimento del compito.

Azioni a livello operazionale. Potrebbe presentarsi la necessità di prendere decisioni molto rapide, al di sopra dei limiti temporali del paziente (perchè la situazione richiede una risposta immediata ad uno stimolo).

TRAINING DI SPECIFICI SKILLS

Questo approccio è volto ad allenare o riallenare abilità significative dal punto di vista funzionale come la guida dell’automobile, o specifiche attività di tipo professionale. Nello specific skill training, a differenza dell’APT, non c’è nessuna aspettativa che il paziente possa generalizzare le skill (le abilità) apprese e trovare beneficio anche in tasks che non siano state oggetto di riabilitazione.

WORKING MEMORY TRAINING (VMT)

Nel VMT viene utilizzato il training della memoria di lavoro per riabilitare indirettamente anche l’attenzione in pazienti con ictus in fase sub acuta.

L’ATTENZIONE COME PREREQUISITO PER LA RIABILITAZIONE

Dalla letteratura emerge l’importanza dell’attenzione per il recupero e per il mantenimento, non soltanto delle funzioni cognitive, ma anche di quelle motorie. Di fatto vi è scarsa possibilità di intervenire efficacemente sui deficit cognitivi nel loro complesso prescindendo dall’attenzione (McDowd J. M., 2003), e inoltre i deficit di attenzione, quando associati, come spesso accade, ad una compromessa funzione comunicativa causata da deficit del linguaggio, inducono un alto rischio di declino cognitivo (Ballard C, 2003).

Anche il recupero dei deficit motori conseguenti ad ictus dipende fortemente dall’integrità dell’attenzione, in particolare di quella sostenuta, come hanno dimostrato Robertson et all (Robertson, I. H. et all, 1997).

Considerando che l’attenzione risulta molto frequentemente compromessa (Goldberg, E., 2004) nell’ictus, come pure nel trauma cranico , il problema della sua riabilitazione si pone quasi immancabilmente in ogni intervento neuroriabilitativo. ll percorso riabilitativo deve essere tagliato su misura (tailored) perché possa ripondere all’individualità del paziente, e occorre pertanto proporre un approccio globale (Michel, J. A. et all, 2006).

_______________________________

BIBLIOGRAFIA:

Armstrong-James, M., & Fox, K. Effects of iontophoresed noradrenaline on the spontaneous activity of neurones in rat primary somatosensory cortex. Journal of Physiology,1983; 335,427^47.

Aston-Jones G., Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance.Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005; 28: 403-450.

Ballard C, Rowan E, Stephens S, et al. Prospective follow-up study between 3 and 15 months after stroke: Improvements and decline in cognitive function among dementia-free stroke survivors.75 years of age. Stroke 2003;34:2440–4.

Barker-Collo SL, Feifin VL, Lawes CMM. Reducing Attention Deficits After Stroke Using Attention Process Training. A randomizet Controlled Trial. Stroke, 2009 – Am Heart ASSoc.

Barker-Collo S, Feigin VL, Parag V, Lawes CMM, Senior H. Auckland Stroke Outcomes Study Part 2; cognition and functional outcomes 5 years post stroke. Neurology 2010; 75:1608-18.

Bates, E., Wilson, S. M., Saygin, A. P., Dick, F., Sereno, M. I., Knight, R. T., & Dronkers, N. F. (2003). Voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping. Nature neuroscience, 6(5), 448-450.

Ben-Yishay Y, Diller L, Rattok J. A modular approache to optimizing orientation, psychomotor alertness and purposive behavior in severe head trauma patients. Working approaches to remediation of cognitive deficits in brain damaged persons. Rehabilitation Monograph n. 59. New York University Medical Centre: Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, 1978:63-7.

Ben-Yishay, Y., Diller, L., Gerstman, L., & Haas, A. The relationship between impersistence, intellectual function and outcome of rehabilitation in patients with left hemiplegia. Neurology. 1968; 18, 852-861.

Blanc-Garin, J. Patterns of recovery from hemiplegia following stroke. Neuropsychol&gical Rehabilitation.1994; 4, 359-385.

Bench, C. J., Frith, C. D., Grasby, P. M., Friston, K. J., Paulesu, E.,Frackowiak, R. S. J., & Dolan, R. J. Investigations of the functional anatomy of attention using the Stroop test. Neuropsychologia. 1993;31, 907-922.

Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, Parkers KR. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and ins correlates. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 1982;21:1-16.

Broadbent DE. Perception and communication. Elmsford, NY, US: Pergamon Press. 1958; pp. 81-107.

Boman, I. L., Lindstedt, M., Hemmingsson, H., & Bartfai, A. (2004). Cognitive training in home environment. Brain Injury, 18(10), 985-995.

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological review, 108(3), 624.

Botvinick, M., Nystrom, L. E., Fissell, K., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (1999). Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate cortex.Nature, 402(6758), 179-181.

Bush, G., Luu, P. & Posner, M. I. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000; 4, 215–222.

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological review. 2001; 108(3), 624.

Botvinick, M., Nystrom, L. E., Fissell, K., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. Conflict monitoring versus selection-for-action in anterior cingulate cortex.Nature. 1999; 402(6758), 179-181.

Broadbent DE. Perception and communication. 1958; (pp. 81-107). Elmsford, NY, US: Pergamon Press .

Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, Parkers KR. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and ins correlates. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 1982;21:1-16.

Cappa SF, Benke T, Clarke S, Rossi B, Stemmer B, Heugten CM. EFNS guidelines on cognitive rehabilitation: report of an EFNS task force. European Journal of Neurology 2005; 12:665-80.

Carter LT, Oliveira DO, Duponte J, Lynch SV. The relationship of cognitive skills performance to activities of daily living in stroke patients. Am J Occup Ther 1988;42:449-55.

Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Malec, J. F., Langenbahn, D. M., Felicetti, T., Kneipp, S.,Giacino, J. T. Rehabilitation of Attention after Brain Injury. American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine 2002.

Cicerone, KD, Dahlberg C, Kalmar K, Langenbahn DM, Malec, JF, Bergquist TF, Morse PA. Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation recommendations for clinical practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2000; 81: 1596-1615.

Cicerone KD. Remediation of “working attention” in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2002;16:185-95.

Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Malec, J. F., Langenbahn, D. M., Felicetti, T., Kneipp, S., Giacino, J. T. Rehabilitation of Attention after Brain Injury. American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine 2002.

Cicerone KD, Dahlberg C, Malec JF, Langerbahn MD, Felicetti T, Kneipp S, Ellmo W, Kalmar K, Giacino JT, Harley JP, Laatsch L, Morse PA, Catanese J. Evidence–Based Cognitive Rehabilitation: Updated Review of the Literature From 1998 Trough 2002. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005; 86: 1681-1692.

Cicerone KD, Donna M, Langenbahn DM, Braden C, Malec JF, PhD, Kathleen Kalmar, PhD, Michael Fraas, PhD, Thomas Felicetti, PhK, Linda Laatsch, PhD, Harley JP, Azulay J, Cantor J, Ashman T. Evidence-Based Cognitive Rehabilitation: Updated Review of The literature From 2003 Through 2008. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92:519-30.

Coelho CA. Direct attention training as a treatment for reading impairment in mild aphasia. Aphasiology 2005; 19:275-83.

Coffey C. Edward, Cummings Jeffrey L, Starkstein Sergio, Robinson Robert. Stroke – the American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Geriatric Neuropsychiatry (Second ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press. 2000;pp. 601–617.

Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation of Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury, NIH (US National Institute of Health), JAMA. 1999; 282:974-983.

Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature reviews neuroscience. 2002; 3(3): 201-215.

Daniel K, Wolfe CDA, Busch MAB, McKevitt C. What are the social consequences for stroke for working-aged adults? A systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40:431–40.

Dietrich, W. D., Alonso, O., Busto, R., & Ginsberg, M. D. The effect of amphetamine on functional brain activation in normal and post-infarcted rats. Stroke. 1990;27(Suppl. Ill), 147-150.

Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM (May 2008). “Stroke”.Lancet 371 (9624): 1612–23.

Dosenbach NU, Fair D A, Cohen AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2008; 12(3): 99-105.

Duncan PW, Zorowitz R, Bates B, Choi JY, Glasberg JJ, Graham GD, Katz RC, Lamberty K, Reker D. Management of adult stroke rehabilitation care: A clinical practice guideline. Stroke. 2005;38:e100–e143.

Eriksen BA, Eriksen CW. “Effects of noise letters upon identification of a target letter in a non- search task”. Perception and Psychophysics. 1974; 16: 143–149.

Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner M I. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2002; 14(3): 340-347.

Fasotti L, Kovacs F, Eling P, Brouwer W. Time pressure management as a compensatory strategy training after closed head injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2000; 10:47-65.

Feeney, D. M., Sutton, R. L., Boyeson, M. G., Hovda, D. A., & Dail, W. G. The locus coeruleus and cerebral metabolism:Recovery of function after cerebral injury. Physiological Psychology. 1985; 13, 197-203.

Goldberg, E “Frontal Lobes and the Civilized Mind. The Executive Brain.”; traduzione italiana: L’anima del cervello, Torino 2004, pag 198.

Goldberg E. The new executive brain. Frontal lobes in a complex world. traduzione italiana ‘La sinfonia del cervello’ 2010, p.126

Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. London: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Gray, JM, Robertson, I, Pentland, B, and Anderson, S. Microcomputer-based attentional retraining after brain damage: a randomized group controlled trial. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 1992;2:97-115.

Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The uniform data system for medical rehabilitation. Report of first admissions for 1992. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1994;73:51-5.

Harley, JP, Allen, C, Braciszeski, TL, Cicerone, KD, Dahlberg, C, Evans, S et al. Guidelines for cognitive rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation. 1992; 2: 62-67.

Haskins EC, Cicerone K, Dams-O’Connor K, Eberle R, Langenbahn D, Shapiro-Rosenbaum A. Cognitive rehabilitation manual. Translation evidence-based recommendations into practice. American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2012. Pag. 76-83.

Hochstenbach, J. B., den Otter, R., & Mulder, T. W. (2003). Cognitive recovery after stroke: a 2-year follow-up. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 84(10), 1499-1504.

Hyndman D, Pickering RM, Ashburn A. The influence of attention deficits on functional recovery post stroke during the first 12 Month after discharge from hospital. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 2008; 79: 656-63.

Hyndman, D., & Ashburn, A. People with stroke living in the community: Attention deficits, balance, ADL ability and falls. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2003; 25(15), 817-822.

Imamura. K.. & Kasamatsu, K. Acutely induced shift in ocular dominance during brief monocular exposure. Neuroscience Letters. 1988; 88, 57-62.

Kolb, B., & Sutherland, R. J. Noradrenaline depletion blocks behavioural sparing and alters cortical morphogenesis after neonatal frontal cortex damage in rats. Journal ofNeuroscience. 1992;12, 2321-2330.

Johansson BB. Current trends in stroke rehabilitation. A review with focus on brain plasticità. Acta Neurol Scand: 2011 123:147-159. Copiright 2010 John Wiley and Sons A/S.

Kang EK,Baek MJ., Kim S, Paik NJ. Non invasive cortical stimulation improves post-stroke attention decline. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2008; 27:646-50.

Kewman DG, Seigerman C, Kinter H, Chu S, Henson D, Reeder C. Simulation training of psychomotor skills: teaching the brain- injured to drive. Rehabil Psychol 1985;30:11-27.

Klingberg T, Forssberg H, Westerberg H. Training of working memory in children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 2002;24: 781–791.

Klingberg T, Fernell E, Olesen P, Johnson M, Gustafsson P, Dahlstro¨m K, Gillberg CG, Forssberg H, Westerberg H. Computerized training of working memory in children with ADHD – a controlled, randomized, double-blind trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2005;44:177–186.

Koelsch S.A neuroscientific perspective on music therapy. Ann NY Acad Sci 2009;1169:426-30.

Kolb, B., & Sutherland, R. J. Noradrenaline depletion blocks behavioral sparing and alters cortical morphogenesis after neonatal frontal cortex damage in rats. The Journal of neuroscience. 1992; 12(6), 2321-2330.

Kwa VIH, Limburg M, deHaan RJ. The role of cognitive impairment in the quality of life after ischemic stroke. Journal of Neurology 1996;243:599-604.

Lezak M, Howieson M, Loring D. Neuropsychological Assessment. Fourth Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Lincoln N, Majid M, Weyman N. Cognitive rehabilitation for attention deficits following stroke (Review). The Cochrane Library 2000, Issue 4.

Loetscher T, Lincoln NB. Cognitive rehabilitation for attention deficits following stroke (Review). The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 5.

Mahoney FI, Barthel D. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Maryland State Medical Journal 1965;14:56-65.

Marrocco, R. T., & Davidson, M. C. Neurochemistry of attention. Parasuraman, Raja (Ed). 1998; The attentive brain. , (pp. 35-50). Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press, xii, 577 pp.

McDowd, J. M., Filion, D. L., Pohl, P. S., Richards, L. G., & Stiers, W. Attentional abilities and functional outcomes following stroke. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003; 58(1), P45-P53.

Mefford, I., Oke, A., Keller, R., Adams, R. N., & Jonsson, G. Epinephrine distribution in human brain. Neuroscience letters. 1978; 9(2), 227-231.

Michel N.A., Mateer C.A. Attention rehabilitation following stroke and traumatic brain injury. A review. Eur Med Phys 2006; 42:59-67.

Mitchell AJ, Kemp S, Benito-Leon J, Reuber M. The influence of cognitive impairment on health-related quality of life in neurological disease. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 2010;22:2-13.

Moscovitch, M. Cognitive resources and dual-task interference effects at retrieval in normal people: The role of the frontal lobes and medial temporal cortex. Neuropsychology. 1994; 8, 524—534.

Murray LL, Keeton RJ, Karcher L. Treating attention in mild aphasia: evaluation of attention process training-II. J Comm Disord 2006; 39:37-61.

Naghavi, M., Wang, H., Lozano, R., Davis, A., Liang, X., Zhou, M., … & Amini, H. (2015). Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet, 385(9963), 117-171.

Nouri FM, Lincoln NB. An extended activities of daily living scale for stroke patients. Clinical Rehalibitation 1987; 1:301-5.

Nys GMS, van Zandvoort MJE, van der Worp HB, de Haan EHF, de Kort PLM, Jansen BPW, et al. Early cognitive impairment predicts long-term depressive symptoms and quality of life after stroke. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2006:147:149-56.

Olesen PJ, Westerberg H, Klingberg T. Increased prefrontal and parietal activity after training of working memory. Nature Neuroscience 2004;7:75–79.

Pardo, J. V., Fox, P. T., & Raichle, M. E. Localization of a human system for sustained attention by positron emission tomography. Nature. 1991; 349, 61-64.

Park, N. W. Evaluation of the attention process training programme.Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 1999; 9(2), 135-154.

Petersen SE, Posner MI. The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual review of neuroscience. 2012; 35, 73.

Posner, M. I. & Boies, S. J. Components of attention. Psychol. Rev. 78, 391–408 (1971).

Posner, M. I., & Petersen, S. E. (1989). The attention system of the human brain (No. TR-89-1).

Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Quarterly journal of experimental psychology. 1980; 32(1): 3-25.

Ponsford JL, Kinsella G. Evaluation of a remedial programme for attentional deficits following closed-head injury. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 1988;10:693-708.

Ponsford J, Kinsella G. The use of a rating scale of attentional behaviour. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 1991;1:241-57.

Raz A. Anatomy of attentional networks. The Anatomical Record Part B: the New Anatomist. 2004; 281(1): 21-36.

Raz, A., & Buhle, J. Typologies of attentional networks. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006; 7(5), 367-379.

Rinne, P., Hassan, M., Goniotakis, D., Chohan, K., Sharma, P., Langdon, D., … & Bentley, P. Triple dissociation of attention networks instroke according to lesion location. Neurology. 2013; 81(9), 812-820.

Rizzo AA, Schultheis M, Kerns KA, Mateer CA. Analysis of assets for virtual reality applications in neuropsychology. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2004;14:207-39.

Robertson IH, Ridgeway V, Nimmo-Smith I. Test of everyday attention. Bury St. Edmunds: Thames Valley Test Company, 1994.

Robertson IH1, Tegnér R, Tham K, Lo A, Nimmo-Smith I. Sustained attention training for unilateral neglect: theoretical and rehabilitation implications. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1995 May;17(3):416-30.

Roberson IH, Ridgeway V, Greenfield E, Parr A. Motor recovery after stroke depends on intact sustained attention: a 2-year follow-up study. Neuropsychology 1997; 11:290-5.

Rohring S, Kulke H, Reulbach U, Peetz H. Effektivitat eines neuropsychologischen Trainings von Aufmerksamkeitsfunkionen im teletherapeutischen Setting. 2004.

Roland, P. E. Cortical regulation of selective attention in man: A regional cerebral blood flow study. Journal fNeurophysiology. 1982; 48, 744-754.

Rossi AF, et al. Top down attentional deficits in macaques with lesions of lateral prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007; 27:11306–11314.

Sarkamo T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S et al. Music listening enhances cognitive recovery and mood after middle cerebral artery stroke. Brain 2008 ; 131:866-76.

Sarkamo T, Pihko E, Laitines S et al. Music and speech listening enhance the recovery of early sensory processing after stroke. J Cogn Neurosci 2009; Nov 19. PMID: 19925203; doi:10.11.1162/jocn.2009,21376.

Schottke H. (Rehabilitation von Aufmerksamkeits storungen nach einem Schlagenfall – Effectivitat eines verhaltensmedizinisch – neuropsychologischen Aufmerksamkeitstrainings) Verhaltenstherapie 1997; 7:21-3.

Sinotte MP, Coelho CA. Attention training for reading impairment in mild aphasia: a follow-up study. NeuroRehabilitation 2007, 22:303-10.

Simon J R. Reactions towards the source of stimulation. Journal of experimental psychology. 1969; 81: 174-176.

Sivak M, Hill CS, Henson DL, Butler BP, Silber SM, Olson PL. Improved driving performance following perceptual training in per- sons with brain damage. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1984;65:163-7.

Sohlberg M, Avery J, Kennedy M, Ylvisaker M, Coelho C, Turkstra L, & Yorkston K. Practice guidelines for direct attention training. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2000. 11:29-30.

Sohlberg, M. M., Avery, J., Kennedy, M., Ylvisaker, M., Coelho, C., Turkstra, L., & Yorkston, K. Practice guidelines for direct attention training. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2003; Vol.11 Nr.3 pp. XIX-XXXIX.

Sohlberg MM, Mateer CA. Improving attention and managing attentional problems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001; 931(1): 359-375.

Sohlberg M., McLaughling K, Pavese A, Heidrich A & Posner M. Evaluation of attention process training and brain injury education in persons with acquired brain injury. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2000; 22:656-676.

Stam, C. J., Visser, S. L., Coul, A. A. W. O. d., Sonneville,L. M. J. D., Schellens, R. L. L. A., Brunia, C. H. M., Smet,J. S. d., & Gielen, G. Disturbed frontal regulation of attention in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1993; 116, 1139-1158.

Stambrook M, Moore A, Peters LC, Deviane C, Hawryluk GA. Effects of mild, moderate and severe head injury on long term vocational status. Brain Injury 1990;4:183–190.

Stapleton T, Ashburn A, Stack E. A pilot study of attention deficits, balance control and falls in the subacute stage following stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation 2001; 15(4): 437-44.

Stathopoulou S, Lubar JF. EEG changes in traumatic brain injured patients after cognitive rehabilitation. J Neurotherapy 2004; 8:21-51.

Strache, W. Effectiveness of two modes of training to overcome deficits of concentration. Int J Rehabil Res. 1987: 10:141S-145S.

Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935; 18, 643-662.

Sturm W, Willmes K. Efficacy of a reaction training on various attentional and cognitive functions in stroke patients. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 1991; 1:259-80.

Sturm W, Longoni F, Weis S.Functional reorganization in patients with right hemisphere stroke after training of alertness: a longitudinal PET and fMRI study in eight cases. Neuropsychologia 2004; 42:434-50.

Sturm W, Wilmes K, Orgass B. Do specific attention deficits need specific training? Neuropsychol Rehabil 1997; 7:81 103.

Tonelli, M. R. The philosophical limits of evidence-based medicine. Academic Medicine. 1998; 73(12), 1234-40.

Tonelli, Mark R. The limits of evidence-based medicine. Respiratory care. 2001; 46.12 .

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 1992;30:473-83.

Westerberg H, Jacobaeus H, Hirvikoski T, et al. Computerized working memory training after stroke-a pilot study. Brain Inj 2007; 21:21-9.

“The top 10 causes of death”. WHO. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index4.html

The WHOQOL Group. The World Helath Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Social Sience Medicine 1998;46:1569-85.

Whyte J, Vaccaro M, Grieb-Neff P. Psychostimulant use in the rehabilitation of individuals with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2002; 17:284-99

Whyte J, Hart T, Vaccaro M, Grieb-Neff P, Risser A, Polansky M et al. Effects of methylphenidate on attention deficits after traumatic brain injury: a multidimensional, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 83:401-20.

Whyte J, Hart T, Bode RK, Malec JF. The moss Attention Rating Scale for traumatic brain injury: initial psychometric assessment. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2003;84:268-76.

Wilson C, Robertson IH. A home-based intervention for atten- tional slips following head injury: a single case study. Neuropsychol Rehabil 1992;2:193-205.

Witte E A, Marrocco R T. Alteration of brain noradrenergic activity in rhesus monkeys affects the alerting component of covert orienting. Psychopharmacology. 1997; 132(4): 315-323.

Witte E A, Davidson MC, Marrocco RT. Effects of altering brain cholinergic activity on covert orienting of attention: comparison of monkey and human performance. Psychopharmacology. 1997; 132(4): 324-334.

Winkens I, Van Heugeten C, Fasotti L, Wade D. Reliability and validity of two new instruments for measuring aspects of mental slowness in the daily lives of stroke patients. Neuropsychologilacal Rehabilitation. 2009; 19:64-85.

Winkens I, Van Heugeten C, Wade D, Fasotti L. Training patients in Time Pressure Management: A cognitive strategy for mental slowness. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2009;23:79-90.

Witte E A, Davidson MC, Marrocco RT. Effects of altering brain cholinergic activity on covert orienting of attention: comparison of monkey and human performance. Psychopharmacology. 1997; 132(4): 324-334. .

Wood, Rodger LI. PhD. Rehabilitation of patients with disorders of attention. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation: September 1986 – Volume 1 – Issue 3 – ppg 43-53.

Ylvisaker, M., Coelho, C., Kennedy, M., Sohlberg, M. M., Turkstra, L., Avery, J., & Yorkston, K. (2002). Reflections on Evidende-based practice and Rational Clinical Decision Making. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2002; vol 10, number 3, pp XXV-XXXIII.

Zatorre RJ, Chen JL, Penhune VB. When the brain plays music: auditori motor interactions in music perception and production. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007; 8: 547-58.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983;67:361-70.